The glassmaker’s mark “F G Mfg Co” has long been known to collectors but lacked a documented origin. Research completed in January 2026 confirms that bottles bearing this mark on their bases were produced at a short-lived glass factory in Michigan City, Indiana that operated from about 1885 to 1886. Only three examples are currently known, all from Indiana bottlers. The account below documents the factory’s brief operation and disappearance.

Michigan City’s ultimately short-lived glassworks begins not with furnaces or factories, but with Samuel Eddy, a New York born merchant who arrived in Michigan City in 1853 and spent the final years of his life fighting what he called the town’s “dull times.” By the early 1880s, Eddy believed the city stood at a crossroads. Manufacturing was increasingly shifting westward, neighboring towns were industrializing, and Michigan City, once vibrant, was slipping into stagnation.

Eddy was not acting on idle speculation. Nationally, glass manufacturing was migrating away from the East Coast toward regions offering cheaper fuel and raw materials. Indiana, with its surface mined coal fields and expanding rail networks, appeared poised to benefit. Glassmaking at this time was still largely a small unit industry, requiring comparatively modest capital investment. Aside from labor, fuel was the single greatest operating expense, and even small reductions in fuel cost could determine whether a plant succeeded or failed.

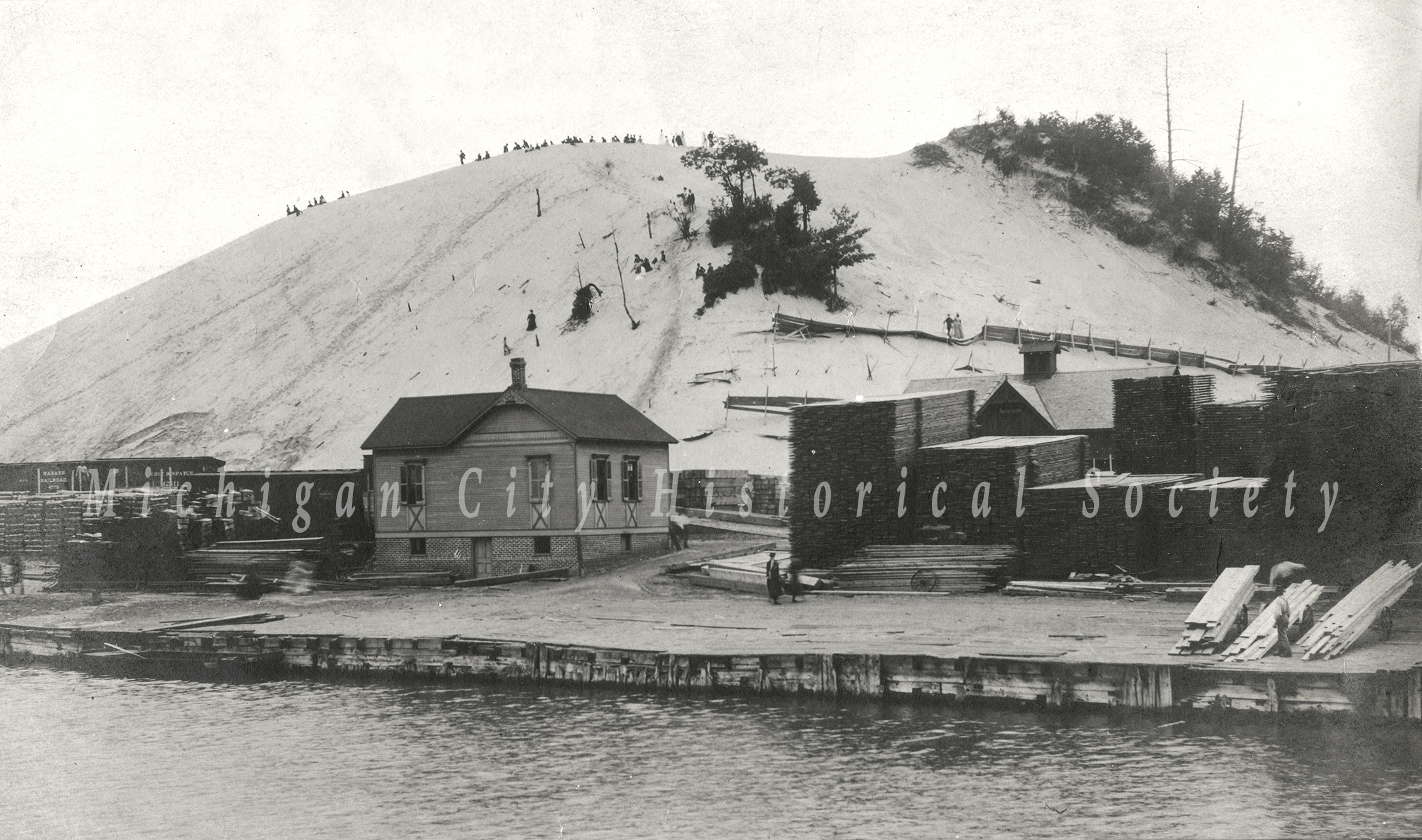

Where many residents saw the towering sand dunes along Lake Michigan as an unavoidable nuisance, Eddy saw opportunity. The most prominent of these dunes, the Hoosier Slide, rose nearly 200 feet and consisted of exceptionally pure silica sand. While townspeople complained of drifting sand filling eyes, streets, and vacant lots, Eddy argued that the dunes represented the city’s last great natural resource.

Beginning in August 1883, Eddy made a series of impassioned public appeals in the Michigan City Evening Dispatch and Michigan City Dispatch. He urged the city to capitalize on its sand by manufacturing telegraph insulators, bottles, fruit jars, sewer pipe, and other glass products, items already in massive demand across the expanding nation. He pointed out that millions of glass insulators were required for the rapidly expanding telegraph system and that other communities were already melting sand into crude “pigs” and shipping it elsewhere for finishing, a process he believed Michigan City could bypass entirely by manufacturing finished goods locally.

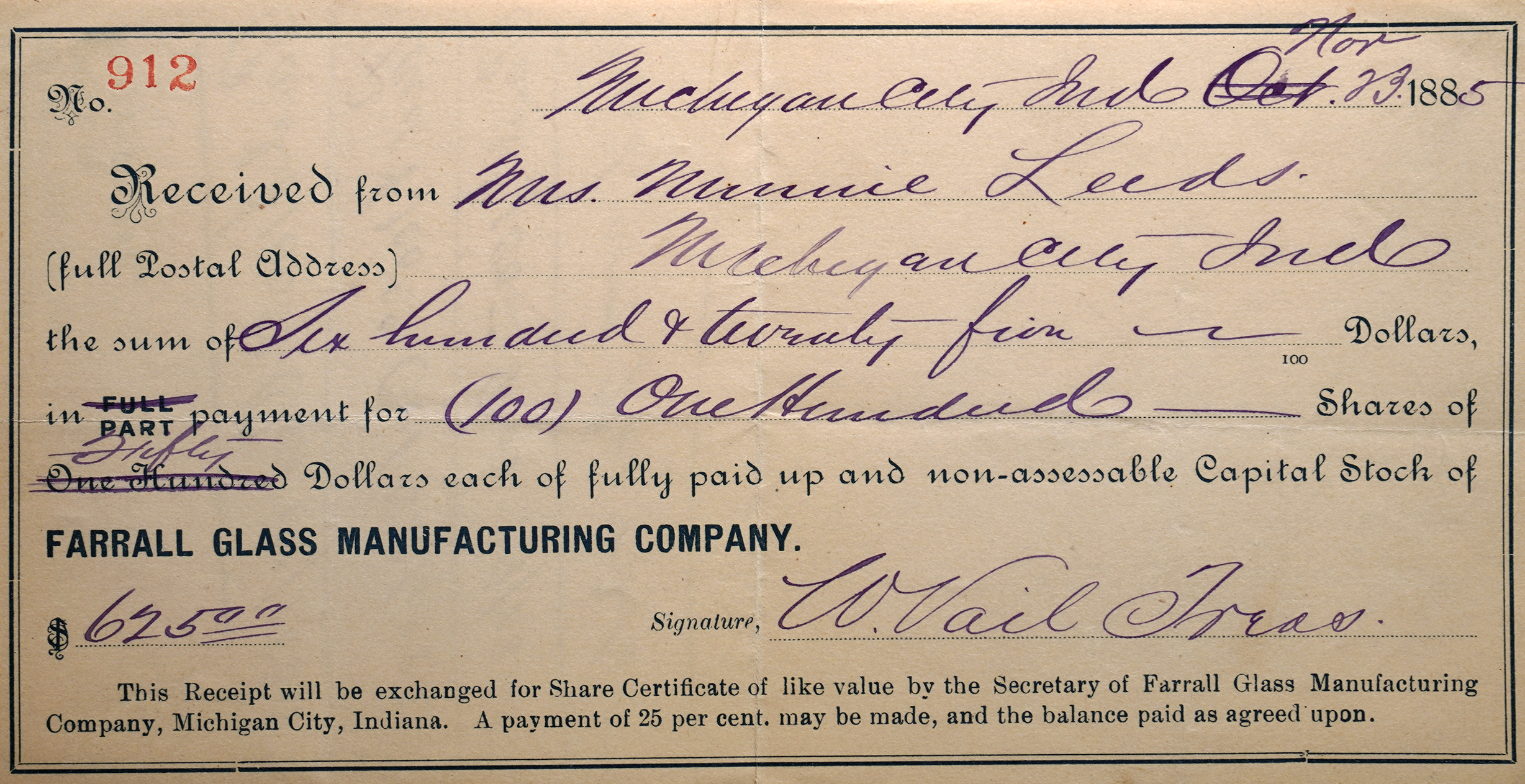

His plan was straightforward and democratic, to form a joint stock company so that working people could buy modest shares and collectively fund a factory. He proposed shares priced at fifty dollars, paid in installments, deliberately structured so that ordinary laborers and small businessmen could participate. This proposal reflected a practical workaround to state corporate law, which prohibited shares below fifty dollars, by allowing shares to be partially paid in advance so that participation remained feasible for wage earners. He insisted the capital required was modest by industrial standards and that success hinged not on outside saviors, but on local resolve.

Despite the urgency of his words, Eddy was met largely with silence.

Two weeks after his first letter, he wrote to The Michigan City Dispatch with a second, far darker plea. In it, he openly shamed the town’s wealthy elite for their inaction, accusing them of allowing their own city to decline through apathy. The sand, he wrote bitterly, mocked the community, filling eyes and vacant lots while its potential wealth went unused. If nothing was done, Eddy declared, he would abandon the effort entirely. His language made clear that this was no longer an abstract economic argument but a moral one, framing industrial development as a civic duty owed to the town’s working population.

Public pressure eventually produced movement, though not without controversy. According to an article from the Michigan City Evening Dispatch dated August 30, 1883, a mass meeting was held at the Armory, where Eddy was elected chairman and Harry B. Tuthill was named secretary. Speeches were delivered by prominent citizens, including Mayor Harvey R. Harris, H. H. Walker, William Kadow, Benjamin Nye, Joseph Garrick, and J. E. DeWolfe. Several speakers openly discussed the steady outflow of local money being spent on glassware manufactured elsewhere, reinforcing Eddy’s argument that a glass factory would immediately serve existing demand rather than create speculative supply.

Subscriptions began to trickle in, and the Dispatch soon published a revised list of donors, dubbed the Roll of Honor. The list revealed a stark divide. The city’s laborers and small tradesmen gave generously relative to their means, while many of Michigan City’s wealthiest figures contributed only token amounts, or nothing at all. The newspaper excoriated these “paltry subscriptions,” warning that without decisive action Michigan City risked becoming “another New Buffalo,” a once promising town that had failed to industrialize and slipped into irrelevance.

The editorial tone grew increasingly severe. One widely quoted Dispatch passage argued that even if the glassworks did not succeed, it would at least demonstrate that the city was alive and willing to fight decline. If men with capital refused to assist, the paper suggested, then they bore responsibility for the town’s stagnation. This public shaming was deliberate and sustained.

William Kadow emerged as one of the most vocal practical supporters of the glassworks during this period. A businessman with firsthand experience purchasing large quantities of bottles, Kadow stated publicly that a single invoice for bottles used in his business had recently totaled approximately $2,000. In other remarks, he estimated his regular annual usage at several hundred dollars. These figures were not contradictory, but rather illustrated both routine consumption and occasional bulk purchasing. His comments underscored one of Eddy’s central arguments, that local industry was not speculative, but necessary to retain capital already being spent by Michigan City merchants.

Among the more notable contributors was Philip Zorn, Michigan City’s brewing magnate. Zorn pledged $200 early on, placing him among the project’s serious backers. His support was not merely civic minded. As a brewer, Zorn depended heavily on a steady and affordable supply of glass bottles, and he understood better than most the economic value of a local glassworks. Zorn would remain connected to the property for decades and would later witness the factory’s transformation from glass production to brick manufacturing.

Other significant supporters included Christopher Roeske, a flouring mill and brickyard operator whose experience with clay extraction and kiln operations made him a particularly valuable ally, Charles “Charley” Kuhs, W. O. Leeds, and several bankers and merchants who gradually formed the backbone of the enterprise Eddy had long envisioned. Despite their efforts, total subscriptions initially stalled at roughly $15,000, far short of what was required. This prompted renewed criticism, suggestions of municipal bond support in the amount of $15,000, and public commentary by City Clerk Martin T. Krueger, known as “Old Bismarck,” who sharply criticized the lack of resolve among local capital holders.

By October 1883, outside observers had begun to take notice. A Logansport newspaper remarked sarcastically that Michigan City wanted to utilize its sand hills and could have them—for a price—mocking the city’s apparent inability to translate natural resources into industry. The commentary underscored a growing regional perception that Michigan City lacked the resolve to capitalize on its advantages.

By late 1883 and into 1884, enthusiasm within Michigan City itself began to wane. A stockholders’ meeting was called for April 12, 1884, at Mozart Hall. When the meeting convened, Harry B. Tuthill, elected chairman, stated openly that he did not know why the meeting had been called. William Blinks then read a technical report by Prof. J. N. Hurty of Indianapolis regarding the quality of Michigan City sand. Despite the favorable findings, the meeting adjourned without resolutions, plans, or a call for further action. In the weeks that followed, no additional meetings were announced, and it appeared that the glassworks project was being abandoned, if not already dead.

After months of stagnation, the project was revived in dramatic fashion. In mid-1884, Samuel Eddy learned, through a newspaper advertisement discovered by the Michigan City Dispatch in a Cincinnati paper, of interest by Theodore D. Farrall, an English-trained glassmaker and chemist seeking a Midwestern site for a major glass manufacturing concern. Subsequent correspondence and a circular addressed to a Lafayette businessman further confirmed Farrall’s intent. Eddy immediately opened negotiations, this time joined by Christopher Roeske, William Blinks, and James S. Hopper.

The negotiations were intense and prolonged. Farrall and his associates received offers from numerous cities, including Chicago, where capital was more readily available. Yet Michigan City’s location on Lake Michigan, its rail connections, proximity to Chicago markets, and abundance of high-quality sand proved compelling. The arrangement was locally heralded as a “million-dollar deal,” contingent upon the raising of a $20,000 local bonus, which was ultimately secured through popular subscriptions.

It is important to note that the Farrall enterprise that ultimately succeeded in Michigan City was not a simple continuation of the earlier Farrall effort, despite contemporary references describing it as a “reorganization.” An earlier Farrall Glass Manufacturing Company had been organized in 1884 as a separate corporate venture, incorporated under the laws of Kentucky with an ambitious capital stock of $1,000,000. Its officers reflected an outside-capital structure, with Thomas C. Woodward as president, George Ames as treasurer, and Theo. D. Farrall serving as secretary and manufacturing manager. During the 1884–1885 business downturn, capital commitments were withdrawn and the Kentucky-incorporated company was allowed to lapse before construction could begin. In the summer of 1885, a new corporation was formed under Illinois law, reusing the Farrall name but operating under a different charter, capitalization, and ownership structure, marking the true beginning of the glassworks that would be built in Michigan City.

The Farrall Glass Manufacturing Company was formally reorganized in the summer of 1885. Contemporary confirmation appeared almost immediately in the Chicago press. On July 25, 1885, the Inter Ocean reported:

“At Michigan City, Ind., the Farrall Glass Manufacturing Company has been organized, under the laws of Illinois, with a capital stock of $500,000. The directors are T. D. Farrall, T. C. Woodward, James S. Hopper, Walter Vail, Christopher Roeske, C. E. DeWolfe, and M. G. Sherman. Stock will be subscribed immediately, and the works will be in operation by Oct. 1.”

The notice confirmed both the scale of the undertaking and its legal structure. While contemporary articles variously described the company as incorporated under Illinois or Kentucky law—reflecting common nineteenth-century strategies for attracting outside capital and avoiding restrictive Indiana statutes—the operating entity ultimately proceeded under Illinois incorporation as a Michigan City manufacturing enterprise.

According to Gwalter C. Calvert, Farrall himself was widely celebrated as both scientist and artist. The Metropolitan Museum of Art reportedly praised him as a worthy successor to the great European glass masters. His reputation lent prestige and optimism to the undertaking and reassured skeptical citizens that Michigan City was attracting talent of national stature.

The company secured a six-and-a-half-block tract west of the Michigan Central Railroad tracks, between Michigan and Fourth Streets. Half of the land was generously donated by Chauncey Blair, president of the Merchants’ National Bank of Chicago. Construction moved swiftly. According to a December 1885 Michigan City Dispatch retrospective, ground was broken on September 10, 1885, and within ten days plans and specifications were approved. Contracts were awarded for furnaces and dry kilns, with William Ohming Sr. submitting the successful bid.

By late December 1885, the plant was sufficiently complete to permit public inspection as final preparations for glass production were underway. Newspaper accounts noted that large crowds were drawn to the site, though such sightseeing was expected to end once regular operations began. The furnaces had been charged and were undergoing the necessary drying and heating process in advance of production. Skilled glassmen from Pittsburgh were present during this period, including Washington Beck, the celebrated mold maker who supplied the plant’s tools and molds, and H. L. Dixon, patentee of the furnaces.

The structure was an imposing brick complex built almost entirely of local materials and by local labor. The main building measured 70 by 70 feet, but with twenty-four annealing ovens attached outside the walls, the working footprint extended to approximately 105 by 105 feet. Twenty-four chimneys pierced the roof. Fire protection was extensive, with city water mains extended to the site, hydrants installed on multiple sides of the building, two hundred feet of hose on hand, and employees organized into a fire brigade. A Michigan Central Railroad siding was extended directly into the works and equipped with a patent elevator, while a large coal shed capable of holding 300 tons ensured an uninterrupted fuel supply.

On January 14, 1886, the works produced its first official melt. The event was witnessed by directors and officers of the company, along with experienced glassmen from Pittsburgh, who declared it one of the finest initial melts they had ever seen.

At full operation, the factory employed approximately seventy-five men, including about twenty union glass blowers working under the Pittsburgh wage scale, often earning as much as $40 per week. Production focused on common green and amber bottles, fruit jars, and druggists’ flasks, with particular emphasis on short-capacity whiskey flasks known variously as jojo, picnic, or shoofly flasks. These bottles were widely used by saloon keepers who purchased whiskey by the barrel and resold it for take-out. Extra-long annealing times, combined with Farrall’s tempering process, were expected to virtually eliminate breakage during steaming, a persistent problem for brewers and bottlers.

For a brief moment, Samuel Eddy’s long-held vision appeared to have been realized in brick and fire, if not in life.

Tragically, Eddy did not live to see the plant reach full operation. He died on July 15, 1885, as construction was nearing completion. His obituary noted that he was born in Troy, New York, in 1823, that his funeral was held at Mozart Hall, and that the Odd Fellows Lodge conducted the rites. It credited him as the originator and father of the glassworks, emphasizing that its earlier failures were no fault of his and that he lived long enough to see the works finally on the way to success.

The glassworks’ downfall came swiftly and from a direction Samuel Eddy could never have predicted. Beginning in the summer of 1886, Indiana was swept up in a frenzy of natural gas speculation.

To the south, in what became known as the Indiana Gas Belt, cities such as Muncie, Anderson, and Kokomo struck enormous deposits of natural gas in the Trenton limestone. These towns ignited flambeaux wells that burned day and night, signaling what appeared to be a new era of industrial supremacy. Gas was cheap, abundant, and transformative. For glass manufacturers, who spent more on fuel than on almost any other overhead, the lure was irresistible. Entire industrial districts relocated with remarkable speed to take advantage of the free fuel offered by Gas Belt municipalities.

Michigan City, however, was left out.

While Muncie later attracted the Ball Brothers and their massive fruit jar operations, drilling efforts in Michigan City produced only foul-smelling marsh gas and uncontrollable artesian wells. Geologists, including Dr. A. J. Phinney, had warned that the Trenton limestone did not extend into northern Indiana, and those warnings proved correct. Without access to the free energy powering kilns in Muncie and Kokomo, the Farrall plant faced a fatal disadvantage.

Compounding the problem were costly design choices and weak management. Contemporary accounts reveal that, after examining the company’s profit-and-loss statements, officials concluded the plant had cost several times more than necessary and that Farrall’s ovens could not be operated profitably on coal. Farrall, widely admired as an artist and chemist, was increasingly regarded as ill-suited to the practical demands of managing an industrial works, while Judge T. C. Woodward was bluntly described as “utterly useless.”

Criticism also focused on furnace selection. Farrall had insisted on installing the Dixon patent furnaces at considerable extra expense. Calvert later observed that the Dixon system performed poorly when fired with coal and was best suited to natural gas, placing Michigan City at a disadvantage just as the state’s gas boom accelerated elsewhere.

Financial pressure mounted quickly. Period accounts describe weekly operating expenses approaching $1,000 and a persistent shortage of working capital, forcing the company to borrow almost immediately after production began and to seek additional funds simply to continue operating.

When the works shut down for the customary summer suspension in 1886, they never reopened. In Calvert’s words, “the handwriting was on the wall.” The building that had housed Samuel Eddy’s dream fell silent, and for the next decade drifting sand gathered against its empty walls.

For nearly a decade, the abandoned glassworks stood half buried in drifting sand, its rail spurs removed and its interior stripped. The same winds that once promised prosperity now piled the Hoosier Slide’s sand against its empty walls.

In 1895, the property found a new purpose when it was acquired by the Michigan City Stone Brick Company. A surviving gold bond issued by the company that same year confirms its attempt to establish brick manufacturing at the former glassworks site. The purchase price was reported as $5,000, and the transaction was consummated by H. B. Tuthill.

The plant was converted using machinery supplied by the Penfield Brick Machine Company and powered by a 100 horsepower steam engine. Conveyors, elevators, and rotary screens replaced blowing irons and annealing ovens, and the sand once intended for glass was crushed and molded into brick instead. Visitors on the day of conversion included Judge Lay of Chicago, C. E. Brice of Washington, D.C., and B. E. LaDow of Willoughby, Ohio. Former owners present included Philip Zorn, Christopher Roeske, W. O. Leeds, A. T. Vreeland, and James B. Hoppe.

Despite early optimism, the brick venture was short-lived. On January 31, 1896, the Fort Wayne Daily News reported that the Michigan City Stone Brick Company had been closed by the sheriff following legal action initiated by the Rice Machine Works of Chicago. Reported liabilities totaled approximately $40,000, indicating severe financial distress.

The following summer, the Chicago Tribune reported on August 9, 1896, that the company’s property would be sold at public auction to the highest bidder. Shortly thereafter, the Indianapolis News reported on December 7, 1896, that S. D. Haskell of Chicago had purchased the plant for $7,500 in cash.

As later recalled by Gwalter C. Calvert, the brick plant initially promised to become the success the glassworks never was. However, no direct documentation has yet been found that clearly records the physical disposition of the original Farrall glass factory building. The structure does not appear on the 1899 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, nor is it visible in any known photographs dated after 1900.

By the time of the 1905 Sanborn map, the site is identified as belonging to the United States Brick Corporation. That map notes the building as drawn from plans and depicts a substantially different layout, suggesting that the original glassworks structure had either been heavily altered or replaced entirely by that time.

The final irony lies in the fate of the sand itself.

Although Michigan City failed to sustain a glass industry, the Hoosier Slide’s 90 percent pure silica sand became a global commodity. Railroads wrapped tightly around the dune as companies hauled its sand away by the carload. Firms such as Ball Brothers, Pittsburgh Plate Glass, and Hemingray shipped millions of tons for fruit jars, plate glass, and telegraph insulators, some as far away as Mexico.

By the end of World War I, an estimated 13.5 million tons of sand had been removed. The Hoosier Slide, once Indiana’s most famous natural landmark, was completely gone.

Samuel Eddy’s vision had been sound, if tragically ill timed. He understood the value of Michigan City’s sand long before others did. Yet cheap gas, shifting industrial economics, and human misjudgment combined to undo his dream. As Calvert later reflected, Eddy would likely have admitted the failure honestly, but he would also have recognized that powerful resources, once unleashed, can reshape cities, industries, and even nations, for better or worse.

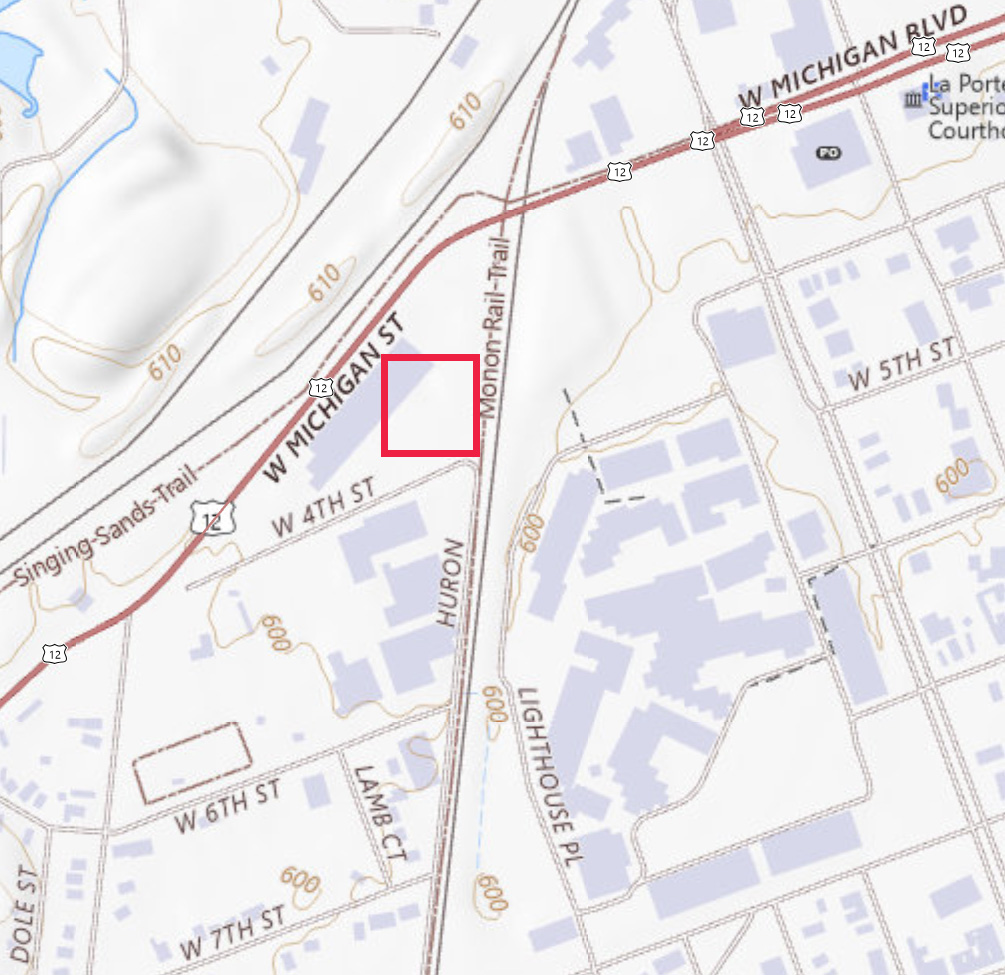

Pinpointing the precise location of the former glass factory is possible thanks to the 1889 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, which includes street and railroad layouts that still exist today.

Based on that map, the factory stood at the corner of West 4th Street and the north end of Huron Street, just west of the railroad tracks that remain in place today, adjacent to what is now the Lighthouse Place Premium Outlets. In modern terms, the site corresponds closely to the area around 700 W. Michigan Boulevard, which occupies roughly the same footprint as the original glassworks.